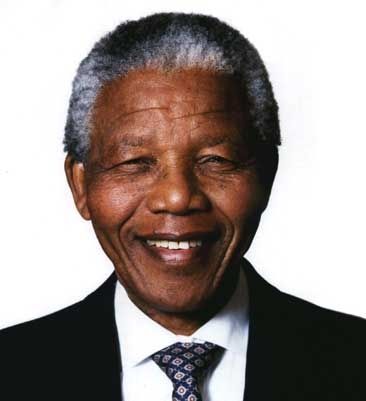

Nelson Mandela: an essential biography

Nelson Mandela was born on 18 July 1918 into the royal family of the Thembu, a Xhosa-speaking tribe which nestles in a fertile valley in the Eastern Cape. There in the family kraal of white washed huts, the young boy spent a happy and sheltered childhood, and listened eagerly to the stirring tales of the tribal elders. His Xhosa name, Rolihlahla, has the colloquial and rather prophetic meaning “trouble-maker”, and he only received his more familiar English name, Nelson, on his first day at Healdtown, a British colonial boarding school.

Nelson Mandela was born on 18 July 1918 into the royal family of the Thembu, a Xhosa-speaking tribe which nestles in a fertile valley in the Eastern Cape. There in the family kraal of white washed huts, the young boy spent a happy and sheltered childhood, and listened eagerly to the stirring tales of the tribal elders. His Xhosa name, Rolihlahla, has the colloquial and rather prophetic meaning “trouble-maker”, and he only received his more familiar English name, Nelson, on his first day at Healdtown, a British colonial boarding school.

The teacher apparently chose English names at random for each unsuspecting child in her class, and was possibly thinking of Lord Nelson at the time, since the famous seagull hadn’t arrived yet; but that would only be a guess. The school principal, ironically, was called Wellington, and frequently informed young Mandela and his classmates that there was no such thing as African culture, and that they, the natives, were indeed privileged to be educated by such a fine and civilized Englishman as himself.

Already it was clear that nobody was going to tell this young man what to do, and when he discovered, on his return home, that his tribal chief and caretaker had decided it was time for him to marry a suitable girl, for whom labola (payment for marrying a girl of African decent) had already been paid, Nelson Mandela took the gap and ran away to Johannesburg.

Thus, at 22, he found himself working as a mine policeman, knopkiere (stick with knob at end) and whistle in hand, at Johannesburg’s Crown Mines. Contrary to his expectations of grandeur, the Mine offices were rusted tin shanties in an ugly, barren area, filled with the harsh noise of lift-shafts, power drills, and the distant rumble of dynamite. Everywhere he looked he saw tired-looking black men in dusty overalls.

Fired with ambition and determination, he completed his law degree through the University of the Witwatersrand, and with Tambo set up South Africa’s first black law firm. Thus began the dangerous and dedicated life of full time struggle against the evils of apartheid. Mandela involved himself wholeheartedly in leading a non-violent campaign of civil disobedience, helping to organize strikes, protest marches and demonstrations, encouraging people to defy discriminatory laws.

Inevitably, as the people’s rage increased and repression cracked down, Mandela was eventually arrested for the first time in 1952, and experienced the other side of the dock, no longer an attorney, but now the accused. He was acquitted, but further harassment, arrests and detention followed, culminating in the infamous Treason Trial in 1958. A full four years after the trial began, Mandela gave his impassioned and articulate testimony, and was found not guilty and discharged. Until this time he had somehow managed to maintain his legal practice, but after the trial, with heightened repression and the banning of the ANC, armed struggle became the only solution.

In 1962 Mandela was arrested for treason again, and sentenced to five years in prison. He made it quite clear that he was guilty of no crime, but had been made a criminal by the law, not because of what he had done but because of what he believed in. While serving this sentence, he was again charged with sabotage, and the Rivonia trial began. His eloquent and stirring address, lasting 4 hours, ended with his famous words: “I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

At forty-six years of age, he first entered the small cramped cell in Section B that was to be his home for so many years to come. It had one small barred window, and a thick wooden door covered by a barred metal grille. He could walk the length of the cell in three paces, and when he lay down, he could feel the wall with his feet and his head.